A Blended Renaissance of Aviation and Aerospace Opening Up More Opportunities

10 Nov, 2020

There is a sort of re-emergence of the aviation and aerospace industry, as more developments begin to blur the line between aerospace and aviation work within the industry, along with a fast-rising renaissance of commercial space development that has been pushing the envelope of an invigorated aerospace industry especially in the United States.

We live in a world where, for 20 years now, at any one time, a human, or a group of humans, have lived off the planet, 250 miles up, cruising around the Earth at five miles a second, on the International Space Station (ISS). So far, 240 humans from 19 countries have called ISS home.

A whole generation of humans are accustomed to the idea of a man living and working in space as just another occupation. But there are bigger plans.

One of the biggest movers and shakers in the aerospace industry is Elon Musk and his company, SpaceX, which is on track to fulfilling a vision of making mankind an interplanetary species by traveling to and setting up a colony on Mars—a planet currently inhabited by robots sent by the U.S.

Musk proposes a plan that would reduce current costs of getting humans to Mars to around $100,000-$200,000 per person—“roughly equivalent to the median price of a house in the U.S.”—and is building and testing a rocket now that would transport 100 people at a time to Mars. Fuel and other needed resources would be created on Mars.

Workforce and Business Development

A world university academic ranking company reported that five countries claim 82 percent of the 2019 top world universities in aerospace engineering: United States, at 34 percent; China, 20 percent; United Kingdom, 14 percent; Italy, 8 percent; and Canada, 6 percent.

According to the Aerospace Industries Association (AIA), at nearly 2.2 million strong in 2019, aerospace and defense (A&D) workers represented 1.4 percent of America’s total workforce, or 2.2 million workers, in 2019.

This was a nearly five percent increase in the total industry workforce from 2018.

Around 58 percent of industry employment was attributed to the aerospace supply chain. Of end-use A&D companies, commercial aerospace held the largest share of employees (49 percent of that total).

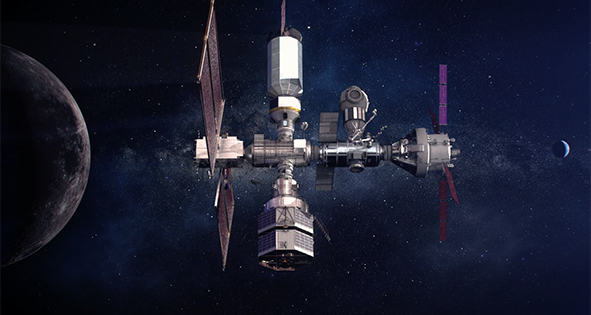

Illustration of the Gateway. Built with commercial and international partners, the Gateway is critical to sustainable lunar exploration and will serve as a model for future missions to Mars.

The A&D industry saw business growth in 49 states and the District of Columbia in 2019, including in Wyoming (21 percent), Vermont (15 percent), South Carolina (12 percent), Missouri (11 percent), and Nevada (11 percent).

Washington state remained the national hub of the A&D industry, accounting for 15 percent of all U.S. A&D industry sales with $137 billion in statewide revenue. It was followed closely by California at $119 billion in A&D revenue, with Texas, Connecticut, and Arizona trailing not far behind.

Other Economic Development

Many of the world’s largest aerospace and defense companies have a significant presence in Arlington, Virginia, including Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Raytheon Technologies.

But Florida is still the key state in aerospace and aviation. In fact, Boeing moved its space and launch division headquarters from Arlington to Titusville, Florida, one of the five Boeing locations in Florida, in late 2019 to be closer to the action.

The company also created a $3 million scholarship program at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University.

The move was driven in part by Boeing’s work on NASA’s Artemis program to get astronauts back to the moon by 2024.

Nearly 106,000 Floridians work in Florida’s aviation and aerospace industries, including rocket scientists, machinists, pilots, engineers, and other advanced technology workers. There are over 540 aerospace companies, 1,780 aviation companies, 20 commercial service airports, two space ports, and 130 public use airports in the state.

In addition to Boeing in Florida are Embraer’s North America headquarters in Fort Lauderdale, which just expanded its business jet service center there; Piper Aircraft, headquartered in Vero Beach, Florida; the 110,000 square foot Airbus Training Center in Miami; Lockheed Martin; GE Aviation; plus both the Elon Musk aerospace company SpaceX and the Jeff Bezos aerospace company, Blue Origin.

United Launch Alliance, which has had a record of 135 consecutive launches since 2006, is also based in Florida.

The Design Renaissance

What is particularly exciting about aviation working in aerospace is a new line of commercial supersonic jets being developed to create a new era of supersonic travel (the supersonic commercial jet, the Concorde, was retired in 2003 in part because of sonic booms causing environmental damage).

A new supersonic business jet is being developed now at Aerion Corporation, headquartered in Reno, Nevada with a new global headquarters in Melbourne, Florida. Aerion’s new supersonic business jet, the AS2, will be manufactured in 2023 and take flight in 2025.

The AS2 is the first supersonic aircraft designed to be powered by 100 percent synthetic fuel and reach supersonic speeds without the need for an afterburner. The 8-10 passenger business jet has a maximum speed of Mach 1.4—or approximately 1,000 miles per hour—flying at 57,000 feet.

An order for the manufacture of 300 AS2s has already been placed by various aviation companies. One of those companies, FlexJet, a private jet ownership and leasing company, put in a firm order for 20 AS2s in November, 2015.

The AS2 will be the first aircraft to be assembled at the Aerion’s new global headquarters in Melbourne. The company is working with partners Lockheed Martin, GE Aviation, and Honeywell.

One of the reasons supersonic jets are making a comeback is because of new technologies designed to reduce the effect of the sonic boom. Sonic booms from jets flying over land were common during the height of the cold war in the early 1960s, rattling windows and shaking glasses in cabinets. The space shuttle generated a sonic boom on its way down for a landing.

Tim Etherington, a pilot and flight deck design engineer at Rockwell Collins for 30 years now working at NASA Langley in Virginia, says that there is a lot work going on to allow a supersonic jets to fly over a number of cities. NASA is now collecting citizen comments.

ZEROe is an Airbus concept aircraft. In the blended-wing body configuration, two hybrid hydrogen turbofan engines provide thrust. The liquid hydrogen storage tanks are stored under the wings.

NASA and the FAA want to come up with a new noise regulation to allow supersonic flights over land.

Etherington explains that there is a way to mitigate the sonic boom, effectively “bending” the boom sound above a certain altitude to refract it back rather than reach the ground. “That is called Mach cutoff, which is an altitude for a particular day for a particular atmosphere at a temperature, among other criteria,” he says. “If you fly above that altitude, the sonic boom will be dissipated before it reaches the ground. You can calculate that if you know all the characteristics of the atmosphere and fly at the right height.”

Etherington is working on a synthetic vision display design incorporating a sonic boom carpet, using a NASA developed algorithm that includes sonic boom prediction, Mach cut-off, and sound pressure levels calculated for current and modified flights plans.

The algorithm information is transformed into geo-referenced objects, presented on navigation and guidance displays, where pilots can determine whether the current flight plan avoids the generation of sonic booms in noise-sensitive areas. The display depiction is a sonic boom footprint which changes location as the aircraft maneuvers.

These technological and regulatory developments about supersonic jets are coming even as the building of supersonic planes continues. “All of these things are happening at the same time,” Etherington says.

A lot of what is happening now with supersonic jets came out of the hypersonic research, he says, with hypersonic development possibly in the lead. “It could be that supersonic is still not as economically viable as hypersonic,” he says. “It depends on who you talk to. There is still research work done to bring the cost of the hypersonic engine down.”

The Search for Innovations

Another state with a huge presence of aerospace is Ohio, ranked second for aerospace growth by PriceWaterhouse Cooper (PwC) in 2020.

Mary Lobo is the director of technology/incubation and innovation office at the NASA Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio. The Center’s rather grand mission is to “drive research, technology, and systems to advance aviation, expand human presence across the solar system, enable exploration of the universe, and improve life on Earth.”

NASA Glenn is overseeing contracts to develop a power and propulsion system for the Gateway platform, which will be an outpost orbiting the Moon that provides vital support for a sustainable, long-term human return to the lunar surface, as well as a staging point for deep space exploration.

Canada, Japan and the European Union are assisting in developing Gateway as well.

The power and propulsion element (PPE) being developed at NASA Glenn is a high-power, 60-kilowatt solar electric propulsion spacecraft that will provide power, high-rate communications, attitude control, and orbital transfer capabilities for the Gateway.

“When it comes to a sustainable human presence on the Moon, allowing for the kind of return trips and going to different locations on the Moon, having a floating habitat there powered by a thruster system that gives us that high thrust and low fuel demand is critical,” Lobo says.

Searching for More Innovation

As the Gateway project continues to develop, NASA has accelerated its look to outside agencies and companies in recent years to find new ideas. NASA Glenn is part of that.

Lobo says that the Glenn engineers and others in NASA engineering groups are focusing on how to get new ideas created inside of NASA out into the hands of the public. “This is a way of finding out how can we develop technologies using collaboration with industry and academia to solve NASA problems,” she says. “It’s a two way street, as we look to solve our problems for exploration and even for aviation.”

NASA has awarded $3.75 billion to 15,000 research-intensive small business to get the ball rolling: “spark innovation” and “engage the brightest minds”. “It’s NASA’s way of saying, “’Hey, we know that the ideas come from a lot of places,’” Lobo says.

There are serious challenges in going back to the Moon and off to Mars, she says. “There are so many things to check off to have a sustainable presence on the Moon.”

One of those problems NASA needs to solve is how to work on the dark-side surface of the Moon where there is no sunshine and batteries can’t be used. How are we going get power? “We are providing rewards to incentivize the public to try to bring us those ideas,” Lobo says.