Agribusiness Sector Continues Strong Growth

17 May, 2019

There are constantly new technologies being introduced— drones to monitor crop growth, dedicated satellites to monitor weather patterns, production and packaging innovations, and new distribution ideas just to mention a few.

But what really drives the industry is consumer demand, which is trending towards more natural foods presented in an ecologically friendly way, plus better distribution of food product from grocery shelves to consumers.

The U.S. beverage industry alone accounts for a huge part of the global food and agribusiness numbers. The American Beverage Association reports that, with a direct economic impact of $182.6 billion, America’s beverage industry provides $19.8 billion in wages, while beverage companies and their employees, and the firms and employees directly employed by the industry, provide significant tax revenues—$19.1 billion at the state level and $30.0 billion at the federal level.

Farmland availability, farming technology and shifting farm ownership attracting more ownership interests.

The U.S. liquid refreshment beverage market grew again in 2017, with retail sales increasing about 3 percent and volume by around 2 percent, according to newly released preliminary data from the Beverage Marketing Corporation. Beverage-specific factors, such as the continued vitality of the large bottled water segment, as well as more general ones, such as the continuing economic recovery, contributed to the overall increase in liquid refreshment beverage volume, which approached 34 billion gallons in 2017.

The Global View

According to a report from sector analysts at McKinsey, food and agribusiness is a $5 trillion industry that represents 10 percent of global consumer spending, 40 percent of employment, and 30 percent of greenhouse-gas emissions.

Since 2004, global investments in the food-and-agribusiness sector have grown threefold, to more than $100 billion in 2013, according to McKinsey analysis.

Trends To Watch

McKinsey analysts outlined trends to watch in this sector:

- Population growth, urbanization, and increased income in emerging markets. By 2020, more than half of global GDP growth is expected to come from countries outside of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; over half the world’s urban population also will be in emerging economies. “Not only is demand for food in emerging markets expected to rise dramatically because of population and income growth, but also these regions are likely to adopt a rich-country diet—more calories, protein, and processed foods,” market analysts reported.

- Demographic and behavioral change in mature markets. In addition to greater demand for protein, especially coming from China, McKinsey analysts anticipate a trend toward healthier diets. “Consumers are increasingly health conscious and place greater importance on environmental sustainability, most visibly in developed countries but more and more in emerging markets. In response, governments are tightening standards for food production. Demand is rising for healthier functional foods (those that offer benefits beyond basic nutrition, such as lowering cholesterol) and for traceable and certified foods that are guaranteed to meet a certain level of safety and environmental or corporate social responsibility.”

- The productivity imperative. Depletion of natural resources, the impact of climate volatility on crops, and declining productivity gains in agriculture are expected to hinder growth in the world food supply, forcing countries to produce more with less. By 2030, for example, the gap between expected water withdrawals and existing supply may reach 40 percent. “The pressure on water, land, energy, and labor resources will necessitate innovation to enhance agriculture productivity.” McKinsey analysts found that productivity gains have slowed in recent years. “Productivity of major crop yields is now growing by only one percent a year compared with twice that rate in the 1960s and 1970s.”

One new agribusiness technology that has come into play recently is vertical farming—indoor hydroponic farming without the need for huge acres of soil that uses much less water.

Vertical farms are agriculture enterprises are grown operations stacked up from bottom to the top floor of either new or reclaimed warehouses, sometimes in the center of an urban area.

One example of a vertical farm operation is being built in Henderson, Nevada where Green Sense Farms from Portage, Indiana was recently granted a one-acre site in the Pittman area of the city to build Henderson’s first vertical farm, growing lettuce, herbs and baby greens. “We are using that technology because Henderson is in the middle of the desert,” Ken Chapa, interim director of Henderson Economic Development, says, adding the area is home to a large food processing cluster featuring Ocean Spray and others. “This vertical farm allows us to enter into that agri-business economy.”

He says that the impetus for the vertical farming acquisition was the fact that there were two U.S. Department of Agriculture designated “food deserts” in the city of Henderson (a food desert is a part of the country that doesn’t have enough fresh fruit, vegetables and whole foods). “We wanted new ways to access food, particularly on the produce level,” Chapa says. “We are also putting an initiative together to develop some community gardens in those same areas. People are more and more concerned about where their food is coming from and what is in their food, and vertical farming really offers a solution to those concerns,” he says.

- A polarized industry structure, toward both bigger and smaller. Analysts anticipate continued consolidation of firms across the agribusiness value chain as well as the emergence of smaller niche players. Large-scale commercial farming has taken off in places such as Brazil, where commercial farms can top 100,000 acres. In addition, smaller- and medium-size family farms are increasing their purchasing (for example, seeds, crop protection, fertilizer, and machinery) and selling grains, sugar, and ethanol through cooperatives, lowering Yep. transaction costs significantly. “At the same time, there are rising numbers of specialized players, especially on the input side, where technology and intellectual property play a critical role,” McKinsey market analysts report. “Small microbial-fertilizer companies are an- example. In addition, the millions of smallholder farmers around the world are gradually integrating into commercial value chains; among them are coffee farmers in Ghana and cotton farmers in India.”

- Big data and information. Expanded access to and more sophisticated use of information will play an increasingly important role in agriculture. There is exciting potential to use more granular data (for example, data for every ten-meter-by-ten-meter square of a field) and analytical capability to integrate various sources of information (such as weather, soil, and market prices) with the goal of increasing crop yield and optimizing resource usage, resulting in lowering costs.

“In our view, however, there is still significant progress to be made on figuring out a business model that captures value from data at scale,” analysts report. “In part, that is because the data are captured by disparate players in different parts of the value chain (for example, seed companies, equipment manufacturers, traders and software developers).”

Managing and capitalizing on the critical data points is likely to require strategic partnerships and acquisitions, and potentially a reshaping of the industry structure. Monsanto’s $930 million acquisition of The Climate Corporation in 2013 was one of several moves by an agriculture giant. Other companies, like Deere and Company, have announced partnerships on data with input firms. More opportunities could arise in adjacent areas once integrated; comprehensive data become available.

- Potential opportunities for investors. Analysts have identified 24 hot spots that may prove attractive to investors over the next decade and assessed these opportunities on market size, risk, and growth potential, including agriculture, agriculture machinery, precision agriculture, bio pesticides, irrigation, storage infrastructure, microbial fertilizers and others.

What Investors Like

Attorney Marisa Bocci, partner with K and L Gates, a multi-national law firm, handles transactions across the country involving the purchase, sale, leasing and financing of farmland. She says that investors are playing the range of agriculture opportunities. “If you step back to the 35,000 feet view, many of my clients that are investing in farmland are also investing in commodities,” she says. “They are also investing in agriculture technology. They look at this as an asset class of food and agribusiness and commodities, and attack it from different directions.”

These investors also don’t focus on just one geographical area for their investments, she says, but look at a balanced portfolio mix from investments all across the country. “It’s about the crop spread, not the geography spread,” she says.

There are two types of crops they invest in: row crops, that are harvested annually, like corn or soybean, and permanent crops, like orchards and almonds. “The more permanent crops like vineyards in California or apple orchards in Washington or pistachios or almonds, need a lot of infrastructure, and have a 25-30 year investor horizon,” Bocci says. “So as an investor, you have to have the capital to see it through.”

Other factors for investors to consider are labor and water resources, she says. “There is more water readily available on the east coast, for example, while on the west coast, there are states with more water restrictions,” she says.

Bocci says that what is exciting is that 95 million acres of farmland will change hands in the next five years. “That is because of demographic shifts,” she says. “People are getting older, and there are more regulatory pressures about water issues and labor issues.”

She says that 3 to 6 percent of farmland in the U.S is owned by institutional investors, such as the pension fund and high net-worth individuals. “That number is expected to increase by almost 30 percent,” she says, adding that there are more international investors looking to purchase U.S. farmland from China, the Middle East and European countries.

For more information about companies mentioned in this article, visit: hendersonnow.com

Side Note 1

Agribusiness takes root in Maricopa

BY STEVE NARANJO,

Center Director

USDA-ARS, Arid-Land Agricultural

Research Center

BY VINCE THACKER, Interim

Superintendent

University of Arizona Maricopa

Agricultural Center

Agriculture in Arizona contributes more than $23 billion to the state’s economy. Like the State of Arizona, Maricopa’s rich history has its roots in agriculture with the community’s earliest settlers converting raw desert land into fertile soils for growing maize, grain, cotton and other crops.

Maricopa is home to a thriving cluster of agritech industries and research facilities, including state universities, federal research centers, and emerging companies utilizing intelligent crop science to produce clean technology products.

The USDA Arid Land Agricultural Research Center (ALARC) and the University of Arizona, Maricopa Agricultural Center (MAC) are two such operations.

The USDA Arid Land Agricultural Research Center (ALARC) is a 20-acre facility whose mission is to develop sustainable agricultural systems, protect natural resources, and support rural communities in arid and semi-arid regions through interdisciplinary research. Research topics include crop and soil management, integrated pest management, insect and plant molecular biology, irrigation technology, remote and proximal sensing for crop production and improvement, water reuse, crop breeding and physiology, and resilience to global climate change.

Recent research focus includes using proximal sensing based high-throughput phenotyping to accelerate the development of crops with improved tolerance to heat stress and drought, developing new industrial crops such as guayule, development and testing of new irrigation technologies for improved water use efficiency, reuse of reclaimed water for agriculture, gene discovery to identify new targets for pest control application and the development of integrated pest management systems for major pests of cotton and other arid-land crops.

The Maricopa Agricultural Center (MAC) is a 2,100- acre research farm within the College of Agricultural & Life Sciences for the University of Arizona. MAC’s mission is to develop and deliver the best-integrated agricultural technologies for the challenges facing Arizona consumers and agricultural producers. Research focuses on cotton, small grains, alfalfa, and new specialty crops that could be used to provide fibers, oils and pharmaceuticals. The Center also supports extension outreach programs, such as Ag-Ventures, various University classes, Ag-Literacy for all age groups, Maricopa 4-H, and Pinal County Masters Gardeners.

For instance, the cotton integrated pest management and cross-commodity efforts (vegetables, cotton and melons) in insect management have saved cotton growers in Arizona alone more than $5 million over the last 22 years. In addition, MAC researchers have facilitated or are facilitating improvements to insect management (IPM) systems in Australian, Mexican, and Brazilian cotton.

Much of the research is conducted collaboratively between ALARC and MAC and with many other federal, state and industry scientists, and with agricultural producers.

Research facilities and agritech companies are drawn to Maricopa because of the city’s ample available land and water for crop testing under clear sky, heat, and drought conditions. Agriculture is a careful steward of both the land and the water needed to produce crops. Modern technology helps farmers and ranchers use what they need and no more. Water is conserved and less is applied to the fields through drip and other variable flow methods.

Maricopa has a forward-thinking focus on research in both agribusiness and agritech. Organizations like ours locate in Maricopa because the city offers a high-quality of life, highly-skilled workforce and unparalleled opportunities for partnerships.

For more information, please visit www.maricopaeda.com or call 520-316-6990.

Side Note 2

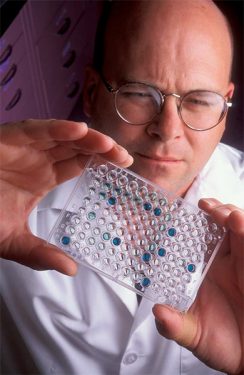

Agriscience at the Hudson Alpha Institute for Biotechnology

How do we increase yields in biofuel plants to improve their potential? How can we make the crops of tomorrow more resistant to drought? What about rising temperatures? At the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, scientists tackle these and other questions on the forefront of agricultural genomics. More than 40 bioscience companies have chosen to establish a presence on the HudsonAlpha campus, taking advantage of proximity to this cutting edge research.

The HudsonAlpha Genome Sequencing Center is one of the few centers in the world performing original sequencing of plants and animals. In the cases of crop species such as sorghum, soybean, cotton, citrus, switchgrass and millet, these genomic references form the basis for genomics-enabled crop breeding to increase yields with faster turnaround times from lab to market.

The center specializes in applying genomic techniques to understand how plants function in response to environmental changes. These efforts are led by Jane Grimwood, PhD, and Jeremy Schmutz. Their work landed both of them on the 2018 Clarivate Analytics list of most highly cited researchers in the world.

The Institute is currently adding a fourth faculty investigator to its agricultural genomics efforts with the goal of uniting HudsonAlpha’s research with Auburn University’s plant breeding and genetics programs.

These types of relationships showcase the potential for Agriscience startups locating at HudsonAlpha – whether in a single co-working space or a lab. The Institute maintains nationwide research relationships with leading institutions in agriculture. It also fosters a unique climate of cooperation between public research and private entrepreneurial efforts.

HudsonAlpha was founded as a nonprofit to combine the power of academic research with the resources of the commercial sector. For over ten years since its founding, the goal has been to bring discoveries to market more quickly, and the Institute has already completed successful tech transfers in pursuit of that goal.

The Institute’s 152-acre biotech campus offers room to grow and access to quality resources, including top talent and a ready workforce, continuous knowledge sharing, and funding sources for intellectual property all in a collaborative community of bioscience enterprises.

The HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology has assembled an incredible team of researchers, partners and associate companies with a common goal. In the world of plant genomics, it’s all about growth.

Related Posts

-

Pinellas County, Florida Celebrates Ribbon Cutting of the ARK Innovation Center Business Incubator

-

Time To “Pivot, Stretch, And Adapt”

-

More Efficient Agriculture Techniques are Coming into the Focus

-

Logistics Getting on a Quicker, more Focused Track

-

Opportunity Zones and Post-COVID-19 Economic Recovery

-

New Ideas Emerge for Both Sustainable and Fossil Fuel Technologies

-

New Goals and New Internet Tech Help Build Base for Advanced Manufacturing

-

Business Services Today Focus on Human Resources, Data Analytics

-

Ready to Shift into High Gear

-

The New Forestry Momentum